The twenty-first century, like every century before it, has produced its own distinct art. The idiosyncrasy of this century is not an art made with a new brush stroke or a new medium. It is the way art is created. For the first time in history, there comes an art that is created without humans.

Algorithms now generate paintings that resemble human work so closely that they compete in galleries and auctions, fetching millions of dollars. This raises a question far more important than authorship: what do we expect art to do in our time?

Art, after all, was never exclusive to humans. A bull etches patterns into the soil as it ploughs. A weaver bird constructs nests of remarkable intricacy. If one were to trace the movement of cells, waves and rhythms would emerge. Flocks of birds sketch fleeting designs across the sky. A forest, taken as a whole, is an elaborate composition of form and balance. Even water in a pond reveals shifting patterns when wind moves across its surface.

If art can arise from animals, natural forces, and now machines, how do we distinguish it from art made by humans? Should human-made art be expected to offer something beyond form and novelty, something more deliberate, more reflective? And from one of the most intelligent species on the planet, is it fair to expect art that not only expresses beauty, but also carries the capacity to influence how we think, feel, and live together on this planet?

Is this expectation from human art too far-fetched, or is it entirely justified? And if it is justified, how well has human art lived up to it since its inception?

Prehistoric cave paintings offer one of the earliest windows into human life. They reflect everyday survival, belief systems, and early social structures. Animals and human figures appear not merely as decoration, but as signs of dependence for food, labour, and ritual meaning. These images suggest that art, from the very beginning, is closely tied to how humans understand their place in the world.

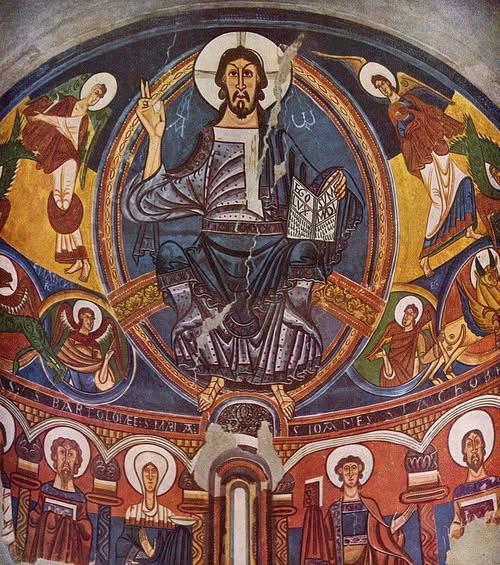

While prehistoric art is fundamental, art historians generally begin tracing organised art movements much later, around the Romanesque period in Europe (roughly 1000–1150 AD). From this point onwards, art became more consciously tied to institutions, power, and collective belief systems. It is here that we can more clearly examine how art participated in building societies, shaping values, reinforcing authority, and occasionally advocating ideas such as order, morality, peace, or justice.

Romanesque and medieval (Gothic) visual art were both deeply shaped by the Church, yet they served society in subtly different ways. Romanesque art functioned as a tool of order and instruction. Its rigid figures, stark hierarchies, and uncompromising imagery reinforced authority, discipline, and fear of divine judgment in a largely illiterate society. It told people what to believe and where they stood within a fixed moral structure.

Gothic art (1150-1500 AD), while still rooted in Biblical narratives and ecclesiastical power, shifted towards emotional engagement. Figures became more human, suffering was made visible, and beauty itself became a means of devotion. Rather than enforcing belief through intimidation, Gothic art drew people in through empathy and awe, encouraging personal faith and inner reflection. Together, they showed how visual art did not merely mirror society, but actively shaped power, morality, and beliefs as experienced by the collective.

Then came the Renaissance (1400- 1700), a period when wealthy merchants and patrons commissioned artists not merely to glorify faith, but to reimagine society through human potential, values, and reason. Visual art and architecture began to shift their focus from the purely divine towards philosophy, inquiry, and the human life. Ideas drawn from thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle found expression in paintings and sculptures.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man reflected a growing fascination with proportion, measurement, and the harmony between the human body and the universe. Michelangelo’s David elevated the strength and resolve of an ordinary human figure, transforming it into a symbol of courage and self-belief. Architecture moved away from excessive ornamentation while retaining essential motifs, enriching spaces with balance, purpose, and clarity. The grandeur of Renaissance architecture lay not in embellishment alone, but in its celebration of human craftsmanship and ingenuity, inviting society to aspire towards magnificence, not only in structures, but in thought and action.

Baroque art (1600-1750) followed with an overt celebration of human achievement. It fed the vanity of kings, aristocrats, and the Church alike, through dramatic compositions, rich ornamentation, and an extravagant use of gold and symbolism. Art became theatrical, designed to impress, overwhelm, and assert authority rather than invite quiet contemplation.

Romanticism (1780–1850) reacted against this excess by turning its gaze towards nature and inner emotion. It sought harmony between humans and the natural world, speaking of beauty, longing, love, and the sublime. Romantic artists treated nature not as a backdrop, but as a force capable of reflecting human emotion and moral struggle.

Impressionism (1865–1885) marked a decisive shift away from grandeur and idealisation. Artists turned to ordinary life, depicting streets, cafés, parks, and fleeting moments of modern existence. This attention to the everyday continued into Realism (1840–1900), shaped by the rise of the industrial working and middle classes. Art began to engage directly with labour, urban landscapes, and social realities, documenting a changing society rather than escaping from it.

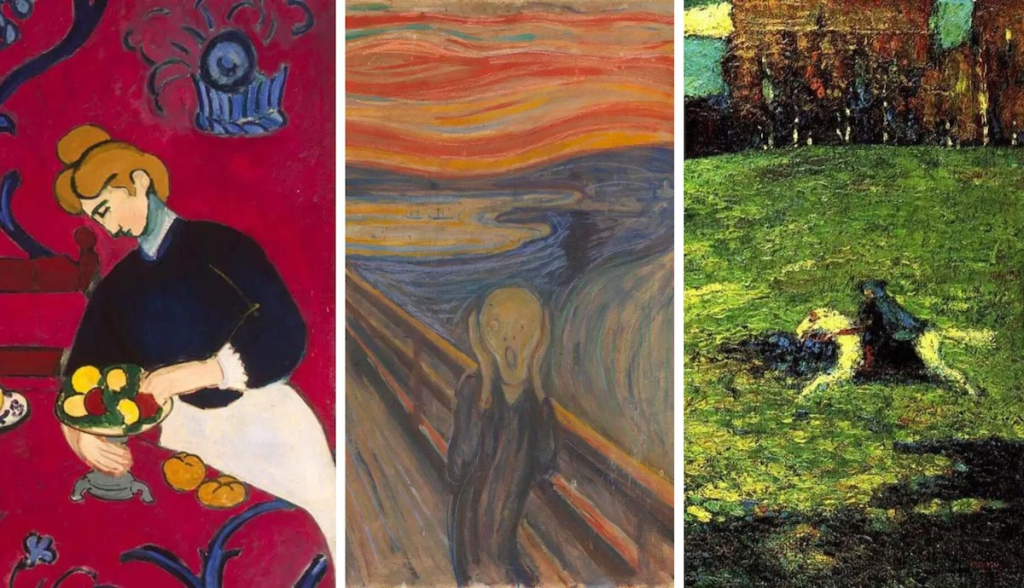

With the emergence of Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and Dadaism in early 20th century, the backdrop was a world shaken by World War I. Much of the art from this period arose as a reaction against academic traditions, rigid aesthetics, institutional authority, and the violence of war itself. Artists broke form, colour, and perspective, not to represent the world as it appeared, but as it felt in a time of rupture.

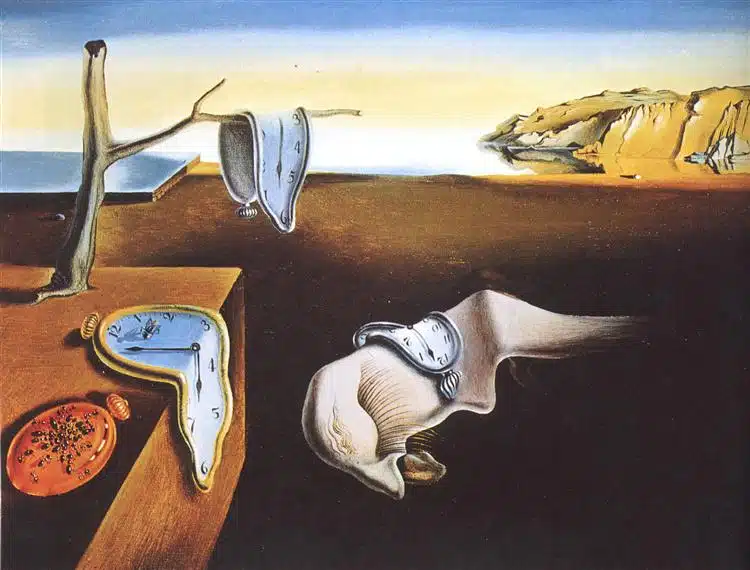

The art in the above period leaned heavily towards subjective experience. It was less about presenting a shared cultural harmony and more about releasing inner unrest, fragmentation, and disillusionment. Expressionism, and later Surreal art, turned inward, attempting to visualise deeper states of the mind and layers of consciousness that lay beneath rational thought. It never leaned towards resolution rather exposed anxiety, contradiction, and the psychology of modern life.

Futurism (1909–1918) turned its attention outward once again, embracing the machine, speed, and the promise of technological progress. Through experiments such as Aeropittura, artists explored aviation and industrial transformation, celebrating flight, velocity, and the exhilaration of modernity. At the same time, Futurist art openly aligned itself with nationalism, technological triumph, and even war, treating conflict as an extension of progress rather than its consequence. This made Futurism one of the few movements that did not merely respond to modernity but aggressively championed it.

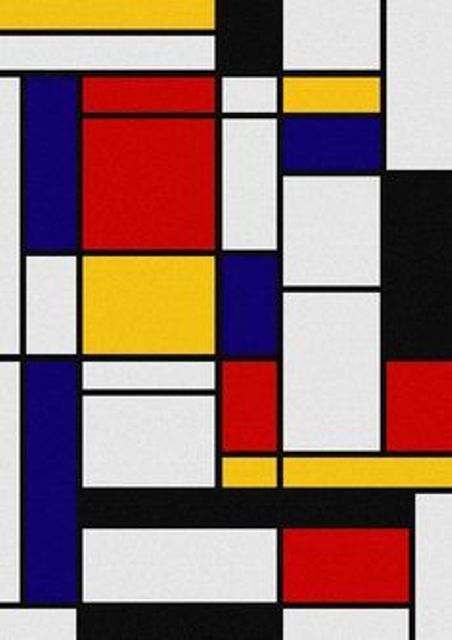

As art moved deeper into modern times, minimalism and abstraction marked a decisive turn inward. Form was reduced, narratives were stripped away, and meaning often rested in personal intention rather than collective experience.

In this phase, art gradually loosened its engagement with broader socio-political realities and began to prioritise individual subjectivism. Minimalism, in particular, distanced itself from emotion, symbolism, and storytelling, offering instead restraint and conceptual clarity.

Contemporary art inherited this inward focus, often privileging idea, process, or identity over universal themes. While this shift expanded artistic freedom, it also raised a question. Has art became more self-referential, did it risk losing its ability to speak beyond the artist to society at large?

Where art once shaped the thinking and direction of societies, contemporary art today appears to struggle for a similar sense of purpose as a shared zeitgeist. If one looks back at the past fifty years, it is difficult to identify moments where visual art has meaningfully influenced the broader trajectory of society. Its participation in shaping collective values or long-term social direction seems limited.

In contrast, modern societies and nations increasingly turn to economics, social sciences, technology, and history to define policy, governance, and progress. Decision-making no longer relies on artistic imagination or cultural vision as a guiding force. Instead art is misused as a propaganda tool for vested interests.

Though art continues to exist and circulate, it no longer appears central to how societies understand themselves or decide where they are heading.

The reason for art not being instrumental in shaping today’s times are:

- Art Market

When a public urinal or an unmade bed with stained underwear and used condoms is elevated to the status of high art, it is not necessarily because these works introduce a breakthrough in thought or redefine the artistic landscape, but because the market validates them. In July 2014, Tracey Emin’s My Bed sold for over £2.5 million. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, first presented in 1917, has since been replicated and sold for millions, with a 1964 edition fetching $1.76 million in 1999, and later versions valued even higher.

Duchamp’s gesture was once radical as it paved the way for conceptual art but the continued recycling of such gestures as market commodities is unsettling. Stripped of their original provocation, these works often generate little meaningful artistic or social dialogue today. Yet prestigious galleries, collectors, and auction houses continue to endorse them. The question then arises. What is being valued? The idea, the context, or simply the price?

The art market, driven by agents, curators, collectors, and auctioneers, increasingly appears to trade on novelty and speculation rather than skill, depth, or artistic rigour. In this process, talent and craftsmanship seem secondary to visibility and sales potential. Almost anything, including the absence of effort or form, can be branded and traded as art, provided there is an art dealer who knows the trick.

This tendency becomes even more apparent in the NFT space. Vector-based chimpanzees, pixelated figures, and algorithmic avatars sell for extraordinary sums, yet offer little in terms of aesthetic, conceptual, or cultural substance. While digital art as a medium holds genuine potential, much of the NFT market functions less as an artistic movement and more as speculative crypto trading. Issues of manipulation, artificial scarcity, and environmental cost further complicate its claim to artistic merit.

As long as the art market continues to reward mediocrity, repetition, and speculation over depth and responsibility, art will struggle to reclaim a meaningful role in shaping contemporary or future society.

2. Artists

There has never been a formal qualification or credential required to be an artist. Art, by nature, remains a medium of expression accessible to everyone. Yet there exists a subtle but important distinction between a creative artist and an artist. The difference often lies in the body of work and the depth of engagement. An artist may release raw emotion onto the canvas, while a creative one processes emotion and adds dimension, frames a proposition, and explores its wider possibilities.

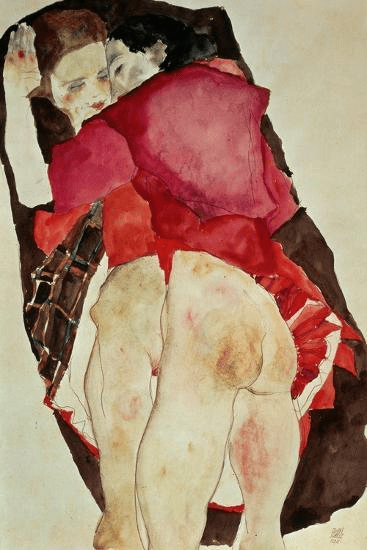

Egon Schiele, one of the most prominent voices of Austrian Expressionism, stands as a compelling example within this debate. Celebrated for his intense draftsmanship and expressive line, he produced some of the most recognisable works of early twentieth-century modernism. His works remain highly valued, a landscape sold for $38.5 million, and one of his drawings fetched nearly $12.3 million. Jane Kallir, in her book Egon Schiele: Self-Portraits and Portraits (2011), describes his figures as deliberately unsettling—bodies contorted, limbs awkwardly positioned, gazes confrontational, and sexuality placed uncomfortably at the centre of the frame.

Schiele’s early works were controversial even in his own time. His use of minors as nude models and his depictions of adolescent girls in implicitly sensual poses, such as Two Girls, Lovers (1911), provoked public and legal outrage. In 1912, he was arrested in Neulengbach on charges related to the public display of erotic drawings accessible to minors and for his involvement with a 14-year-old girl, which was below the age of consent at the time. He served a brief prison sentence, during which one of his drawings was publicly burned by the court.

Accounts of Schiele’s life describe his unsettling fixations, such as his half-disgusted obsession with sexuality and unquenchable sex drive. While his work provided the art market and critics with an incredibly productive oeuvre of Austrian Expressionism, it also raised difficult questions beyond the canvas.

Can an artist whose life remains ethically troubling still offer direction to society? Or does the responsibility of shaping values fall outside the scope of artistic greatness? Is an artist’s legacy confined solely to what is produced on canvas, or does it extend to attitude, philosophy, and the manner in which one inhabits the world?

These questions become increasingly relevant when evaluating whether contemporary art, and contemporary artists are equipped to guide society rather than merely reflect its fractures.

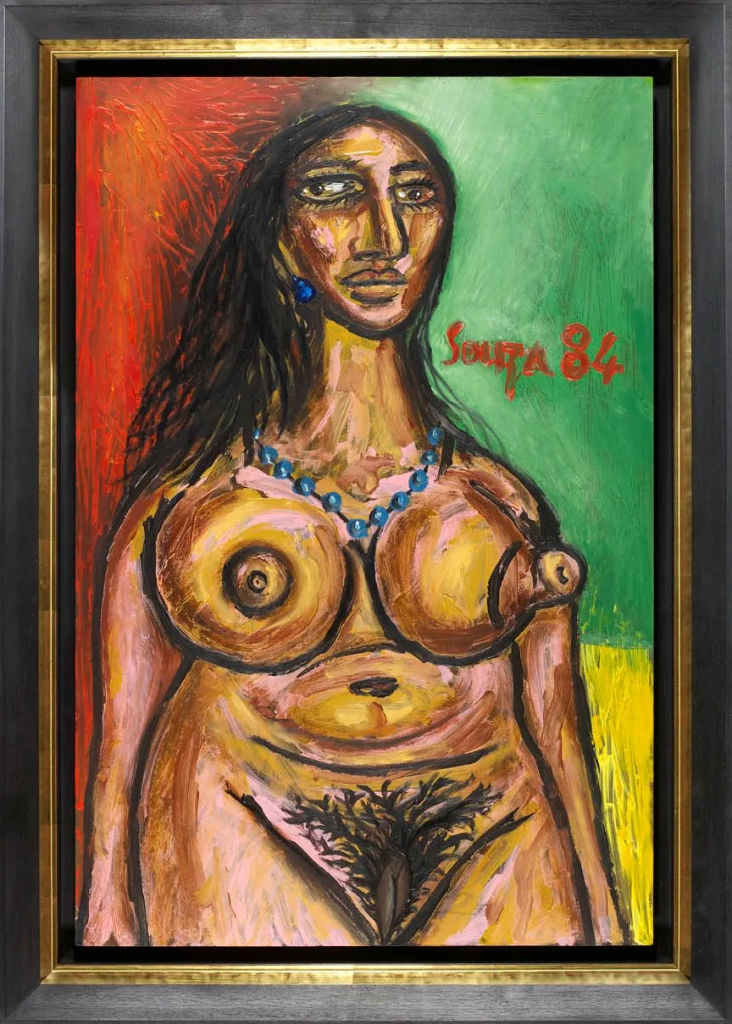

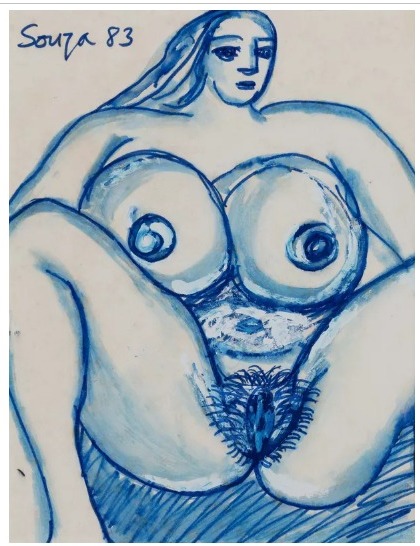

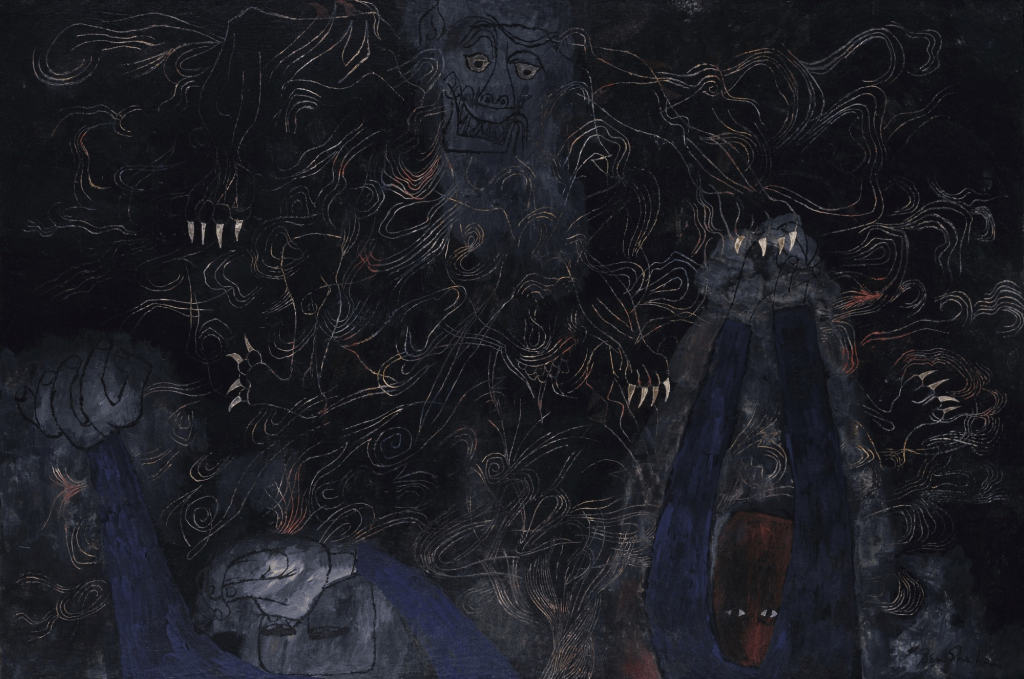

Let us examine the work of another influential modern artist, often described as the Picasso of India—Francis Newton Souza. His paintings command high prices in the international art market, with works selling for millions of dollars. While several of his paintings addressing religion, power, and the human condition are widely regarded as groundbreaking, his nudes remain a persistent point of contention.

Souza openly spoke about experiences from his youth, including secretly watching his mother bathe through a hole he bored into a door. Art critics and biographers have often linked his obsession with distorted, confrontational nudes to guilt, repression, and an intense fascination with the female body. These interpretations place his work firmly within a psychological framework rather than a purely aesthetic one.

Art, undeniably, can be therapeutic. It plays an important role in cognitive and behavioural therapies, offering individuals a way to confront guilt, trauma, obsession, or suppressed desire. An artist or any individual should have the freedom, and perhaps even the encouragement, to express such inner conflicts on canvas as a path toward personal release or healing.

However, a difficult question arises when this private act of expression enters the public realm as art. Souza’s recurring depictions of naked women often exposing their genitalia in deliberately crude, confrontational, and unaesthetic poses may well represent his personal struggle. As therapy, such expression has value. But as a piece of art, does it carry any deeper symbolic, philosophical, or metaphysical meaning?

Do these works evoke sensual sensitivity or aesthetic contemplation? Do they narrate a story, reveal a hidden truth, or offer insight beyond shock and provocation? Or do they remain locked within the artist’s unresolved psychological space?

The art market often frames these works as expressions of eroticism or sexual liberation, praising their confrontational energy and unashamed nudity. But erotic response alone cannot define artistic merit. Pornography, too, evokes eroticism. If provocation is the sole criterion, where does one draw the line between art and explicit content?

Sexual liberation, when meaningfully explored, engages the mind as much as the body. It can be suggested through form, symbolism, intimacy, restraint, or even absence. Renaissance nudes, for instance, carried narrative, philosophy, sacredness, and symbolism. Beauty and aesthetics were not indulgences but tools used to invite contemplation and communicate deeper values about humanity, divinity, and balance. Nudity served a purpose beyond exposure.

This brings us back to a larger, unresolved question. An artist driven by voyeurism or unchecked sexual fixation may still produce work that the market celebrates. But can such work meaningfully contribute to shaping a society? And should artistic greatness be measured solely by what appears on the canvas, or should it also account for the artist’s broader vision, like thoughts, philosophy, ethics, and insight into life?

If art once guided societies toward shared values and collective reflection, perhaps it is worth asking whether the designation of “great artist” today demands more than strokes, colours, and market validation alone.

3. Buyers

For art to reclaim a meaningful role in society, the public must become more visually literate and capable of understanding, questioning, and evaluating art beyond its market value. Unfortunately, the wider audience remains relatively nascent in understanding visual art.

The buyer is no longer a patron deeply engaged with brushwork, form, or artistic process, but part of a broader consumer culture shaped by visibility and influence. Public relations, social media presence, media narratives, and the personal profiling of artists increasingly determine value. Who an artist associates with, where they are seen, and how they are positioned often matter more than what they think, explore, or express through their work.

Even educators and institutions are not immune to this influence; market valuation often becomes a proxy for artistic worth. As a result, works gain prominence simply because they are expensive and widely promoted.

An informed audience would naturally create demand for work that is thoughtful, rigorous, and culturally productive. Without this shift, the art ecosystem risks reinforcing spectacle over substance, and consumption over contemplation.

The time has come when a manifesto for a new art movement is required. A productive art movement.

What is productive art?

Productive art is purposeful both for the artist and for the world it inhabits. It shapes thought, behaviour, and attitude, guiding society towards peace, tolerance, acceptance, mutual respect, and a shared sense of well-being. It communicates without language, sparks connection, creates engagement and participation even between strangers.

Such art does not merely decorate life; it elevates it. It uplifts the spirit, sharpens awareness, and intensifies the experience of being alive. It inspires the imagination to move beyond the familiar, opening pathways to new possibilities, creativity, and innovation. At the same time, it invites introspection, encouraging reflection not only on the self, but on one’s place within a larger human and ecological whole.

In a time when art risks becoming either spectacle, commodity or propoganda, productive art reclaims its responsibility: to contribute meaningfully to the inner and outer life of society.

Every era of art has produced moments of productive art, with the Renaissance often regarded as one of its highest points. Renaissance actively nurtured humanism, drawing from the philosophies of thinkers, and placing human reason, dignity, and inquiry at the centre of visual culture. Its architecture offered more than grandeur; it demonstrated the coexistence of beauty and functionality, shaping spaces that aligned aesthetic harmony with human use and civic life.

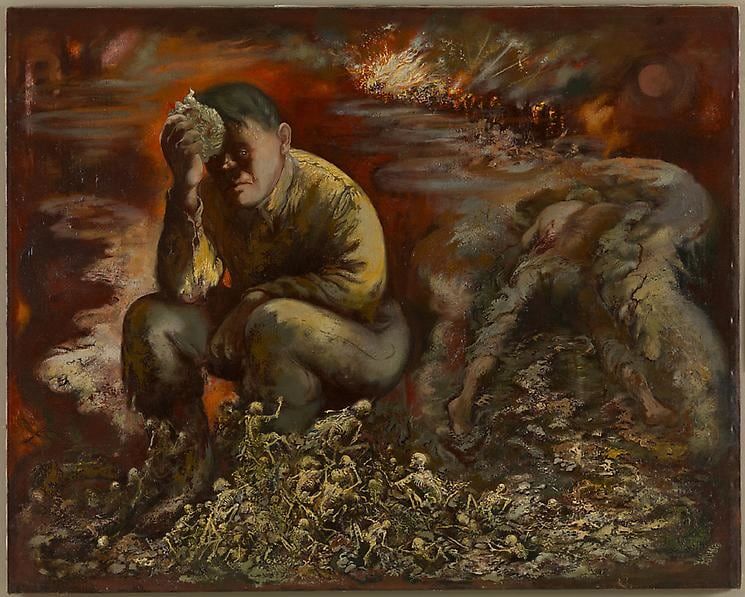

The World Wars, too, generated powerful forms of productive art, giving rise to radical movements and uncompromising artists. German Dadaist George Grosz produced a body of work that fiercely attacked militarism, war profiteering, social hypocrisy, and the widening divide between rich and poor. His drawings exposed corruption and moral decay with brutal clarity. Grosz’s art was so threatening that the Nazis labelled him “Cultural Bolshevist Number One,” recognising the danger posed by images that refused to glorify violence or submit to propaganda.

These moments reaffirm that when art engages directly with the moral, political, and human realities of its time, it does more than reflect history. It actively intervenes in it.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, American painters began to confront social realities more directly. Themes of joblessness, poverty, political corruption, injustice, and the excesses of American materialism entered visual art with renewed urgency.

Ben Shahn emerged as a significant voice during this period. A committed advocate for peace, he openly denounced war and later nuclear weapons. In one of his paintings, he criticised nuclear blast, painting it almost monstrous with clouds of lethal poison. The imagery transforms technological power into a living menace, making visible the moral and human cost of destruction rather than its spectacle.

Productive art is not confined to visual expression alone. It can also emerge through ideas, actions, and ways of living. Mahatma Gandhi, in his role as a freedom fighter, demonstrated a profound form of creative innovation in confronting injustice. At a time when much of the world was consumed by war and violence, he introduced non-violence not merely as a moral stance, but as a deliberate, strategic response to oppression.

Gandhiji’s methods relied on participation rather than force, and altered the conscience of both the oppressed and the oppressor. In this sense, his approach functioned much like productive art- purposeful, transformative, and capable of influencing society far beyond its immediate context.

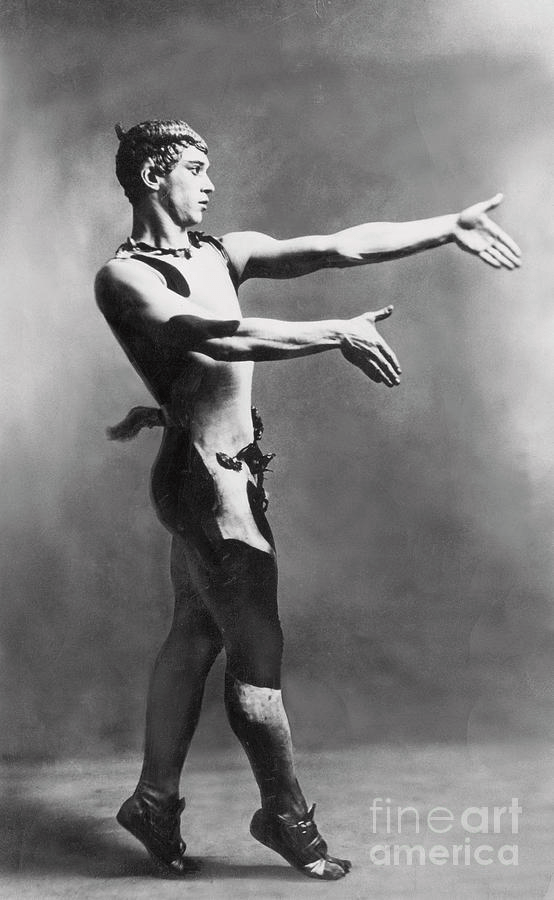

Being productive in art does not require political or socio-economic engagement. Valsan Nijinsky, the legendary Russian ballet dancer, exemplified productive art through innovation in movement. By developing modern ballet, he introduced a raw, tribal energy that moved away from the rigid elegance of courtly dance. In doing so, Nijinsky paved the way for abstraction in dance, inspiring subsequent generations to explore new possibilities in contemporary and modern dance forms. Here, productivity is measured not by social commentary but by the expansion of artistic language and the transformative power of creative expression.

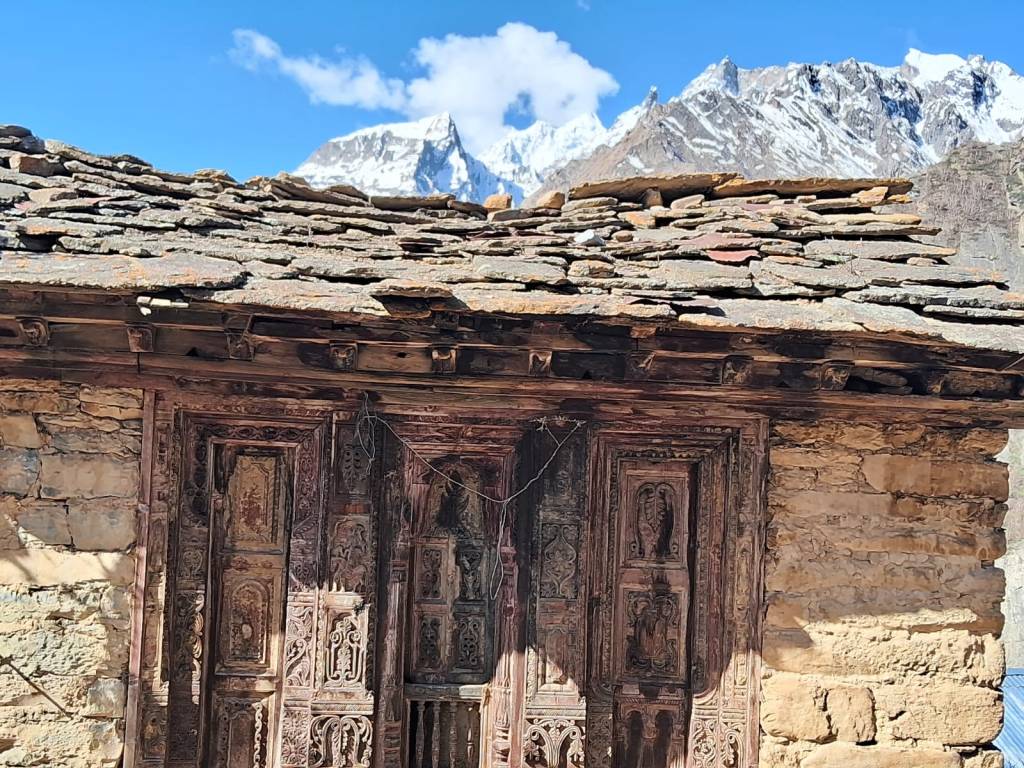

Architect Álvaro Siza Vieira designed the modernist saltwater pool, Piscina das Marés, in Leça da Palmeira near Porto. The facility functions as a public bathing spot, with separate pools for adults and children, changing rooms, and a bar. What sets it apart is how the pools are integrated into the natural rock formations, using the contours of the landscape as boundaries. This minimal yet thoughtful architecture accommodates the needs of modern life while leaving no environmental footprint, all the while retaining a distinctive aesthetic that elevates both function and form. By harmonising functionality, environmental sensitivity, and aesthetic elegance, the pool goes beyond mere utility. It elevates the experience of daily life, fostering reflection, engagement, and a sense of belonging.

Productive art, therefore, is not limited to canvas, stage, or page; it encompasses any creative practice that enriches human thought, behaviour, or perception, whether through movement, structure, or lived interaction with space.

The 2006 film Rang De Basanti became a cultural phenomenon, sparking conversations about civic responsibility and inspiring a generation of Indian youth to question authority and engage actively in social and political issues. Its impact lay not just in entertainment, but in how it mirrored contemporary frustrations and channelled them into a call for action. Similarly, the poetry of Pash, Dhumil, and Dushyant Kumar resonated deeply with the social and political consciousness of their respective eras. Pash’s revolutionary verses challenged entrenched hierarchies and oppression, Dhumil’s sharp satire exposed urban alienation and bureaucratic decay, and Dushyant Kumar gave voice to dissent, hope, and the longing for justice.

The twenty-first century demands a manifesto for a new art movement, the one that is productive not only for people but also for the planet.

The expectation from artists today is not the invention of yet another visual style or a novel way of applying colour, but the cultivation of a new pattern of thought. Style, technique, and formal pattern have become vulnerable territories. When AI encounters a recognisable aesthetic system, whether it is a painterly language, compositional logic, or technical method, it can replicate it, recombine it, and even outperform the original in precision and scale.

The Next Rembrandt exemplifies this shift. The project resulted in a 3D-printed painting generated entirely from data extracted from Rembrandt’s existing body of work. Using deep-learning algorithms and facial-recognition software, developers analysed everything from eye spacing and facial proportions to brushstroke depth and directional rhythm. These measurements informed a predictive model that generated a “new” Rembrandt, executed by a 3D printer with such accuracy that it could plausibly deceive even a trained forgery expert.

AI today can generate artworks in the style of Leonardo da Vinci, Picasso, or Dalí. What it cannot do is think like them. It cannot hypothesise, doubt, rebel, or take moral risk. It cannot arrive at an idea through lived conflict, contradiction, or philosophical inquiry. AI operates within probability; artists operate within consciousness.

For artists who possess original ideas, who think rather than merely produce, this is not a moment of crisis but of opportunity. As AI floods the world with endlessly processed aesthetics, the true scarcity shifts decisively towards original thought. In an age where style can be automated, the exclusivity and value of art will lie not in how it looks, but in why it exists.

Productive art in the twenty-first century, therefore, must move beyond replication and spectacle. It must reassert thought as its primary medium. The thought that questions, disrupts, heals, and reorients humanity’s relationship with itself and the world it inhabits.

THE MANIFESTO FOR PRODUCTIVE ART- THOUGHTISM

(A 21st Century Declaration)

We live in an age of unprecedented production of art and an unprecedented absence of consequence.

Images circulate endlessly. Objects sell for millions. Styles multiply without meaning. Yet art rarely shapes thought, influences behaviour, or contributes to the direction of society. In a world facing ecological collapse, social fragmentation, and moral confusion, art has become largely decorative, speculative, or self-referential.

This declaration calls for Productive Art.

Productive Art is art that creates consequence.

It does not exist merely to be displayed, traded, or consumed.

It exists to engage, question, elevate, and transform.

In the twenty-first century, thought is the primary medium. Hence this movement should be called as “Thoughtism”

Style, technique, and form can now be replicated by machines. Artificial intelligence can imitate masters, recombine aesthetics, and generate infinite variations. What cannot be replicated is original thinking, ethical inquiry, lived contradiction, and conscious intention.

Therefore, the future of art does not lie only in new styles of applying colour, but in new patterns of thought.

Productive Art demands responsibility from the artist.

Emotion alone is not enough. Expression without reflection is insufficient. Personal experience must be processed, not merely discharged, and transformed into propositions that speak beyond the self.

Productive Art refuses validation by price alone.

Markets may circulate art, but they must not define its value. When anything can be declared art solely through spectacle, provocation, or financial worth, meaning collapses. Value must be measured by depth, relevance, and the ability to affect consciousness over time.

Productive Art is not propaganda.

It is not confined to political ideology or social commentary. It may be philosophical, ecological, spiritual, or experiential. Its purpose is not instruction, but transformation.

Productive Art transcends disciplines.

It exists in visual art, cinema, literature, music, dance, architecture, design, and innovation. Wherever creativity reshapes perception and behaviour, Productive Art is present.

Productive Art is sustainable.

No art is productive if it damages the world it inhabits. Creation must acknowledge ecological limits and human interdependence.

Productive Art is not a rejection of contemporary art.

It is a demand for responsibility within it.

Productive Art is intelligence (natural)

As machines master style, artists must master meaning. Artificial intelligence may generate images, but it cannot generate purpose.

Productive Art is engagement not consumption.

Productive Art demands engagement, presence, and reflection of the buyers and not their passive consumption.

We call upon artists, institutions, educators, collectors, and audiences to move beyond spectacle, beyond market validation and reclaim art as a force that shapes consciousness, culture, and the collective future.

Productive Art is not a luxury.

It is a necessity.

Leave a comment