As we drove along the winding mountain roads, my sleepy eyes snapped open at the sound of honking. Through the haze, I noticed the uneven signage of grocery stores, restaurants, clothing shops, and butcher stalls, while clouds of dust from a nearby mountain being levelled blew into my face. For a moment, I felt as though I had never left my city—cramped, chaotic, and forever under construction. Then, through the clutter, my eyes caught a glimpse of a beautiful mountain, now pushed to the background by concrete blocks that my driver casually referred to as the homes of Pithoragarh—the largest city in the Kumaon Himalayas.

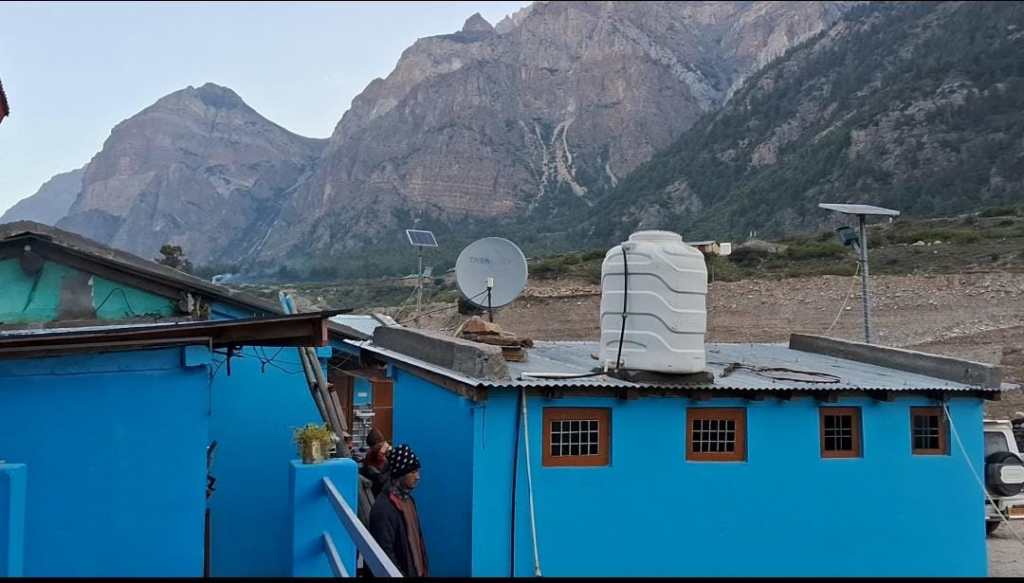

The horror of urbanisation devouring the natural landscape—a horror I thought I’d left behind in my city—had followed me here. It crept through all the grand mountain cities – Dharchula, Shimla, Dehradun, Almora, Solan, Nainital, and seeped even into the smallest villages of once-upon-a-time inaccessible valleys like Vyas Valley, Darma Valley, Tirthan Valley, each aspiring to mimic their concrete-clad counterparts.

While it is important to make these remote villages self-sufficient and prosperous, that goal can never be achieved by imitating cities—it lies instead in preserving their own unique character.

Take, for instance, the ancient villages of Xidi and Hongcun in southern Anhui, China. These UNESCO heritage sites have retained the traditional layout, landscape, architectural forms, and construction techniques of Anhui villages dating from the 14th to the 20th century. While preserving intangible cultural heritage—such as local art, cuisine, customs, medicine, and painting—they have also modernised infrastructure, enhanced connectivity, strengthened ecological safeguards, and improved safety measures. These efforts have fostered a balanced and sustainable model of development, where economy, society, environment, and culture grow in harmony.

Another compelling example is Carina, an abandoned town in Italy that was revived as a tourism hub after an earthquake. Rather than erecting new, often monotonous hotels, the town’s revival focused on restoring old buildings into heritage homestays. This approach brought back local craftsmanship, created a warm, authentic experience for visitors, and provided the essential services expected from modern hospitality. Guests are immersed in the region’s culture through eno-gastronomic experiences, local craft workshops, and community-led events—all within an architectural setting that stays true to the town’s roots.

These villages show that modernisation and development can reach the traditional villages without disrupting their centuries-old spatial pattern and appearance, culture and authenticity, if there is a strong legal and administrative framework.

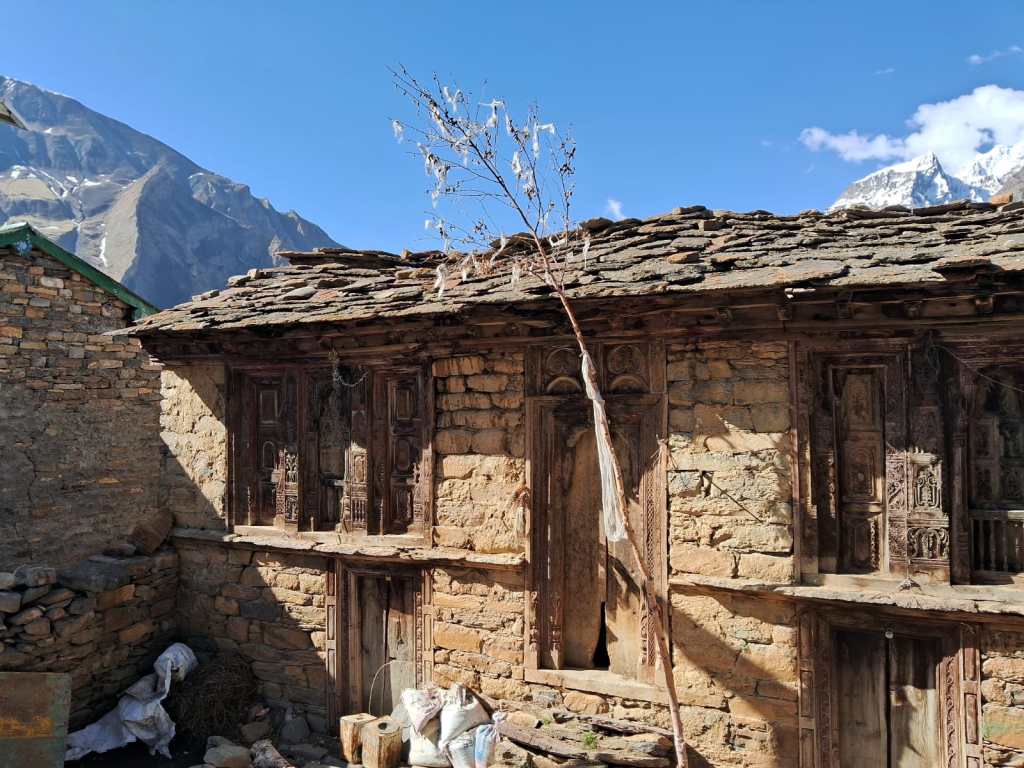

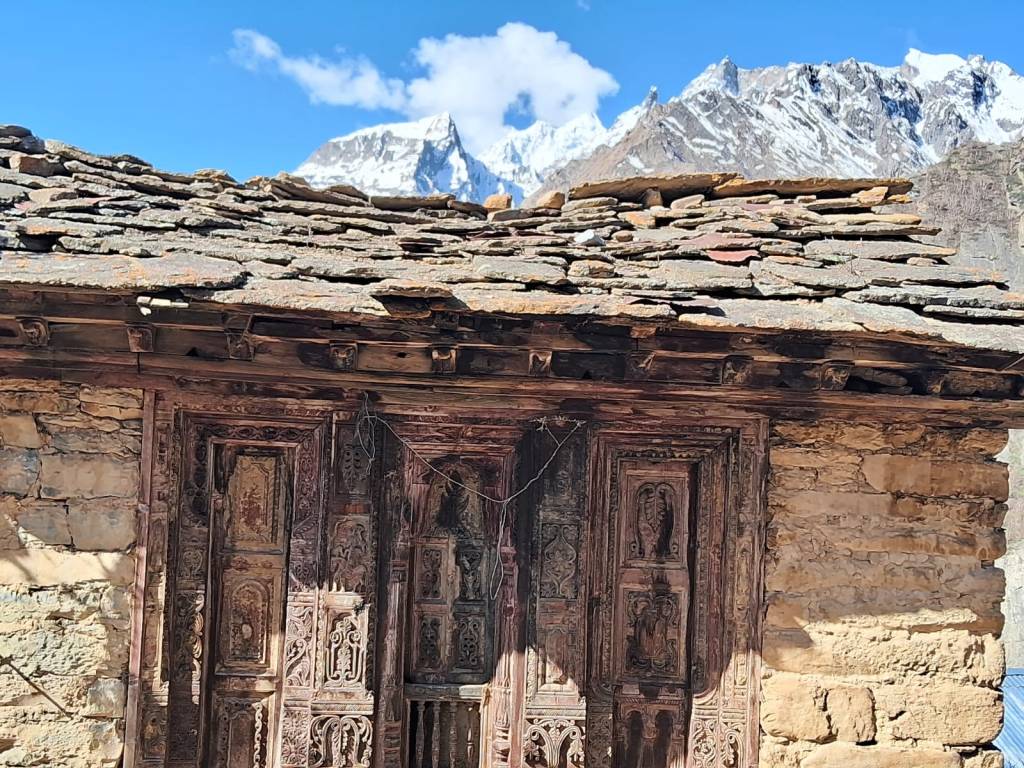

While the beauty of Himalayan villages is unparalleled, their built environment, especially the rapidly growing homestays, often appear philistine, despite the region’s rich cultural heritage. These structures lack the rustic charm that once defined village life, with a noticeable absence of historic architecture, intricate façades, local materials, and traditional building techniques.

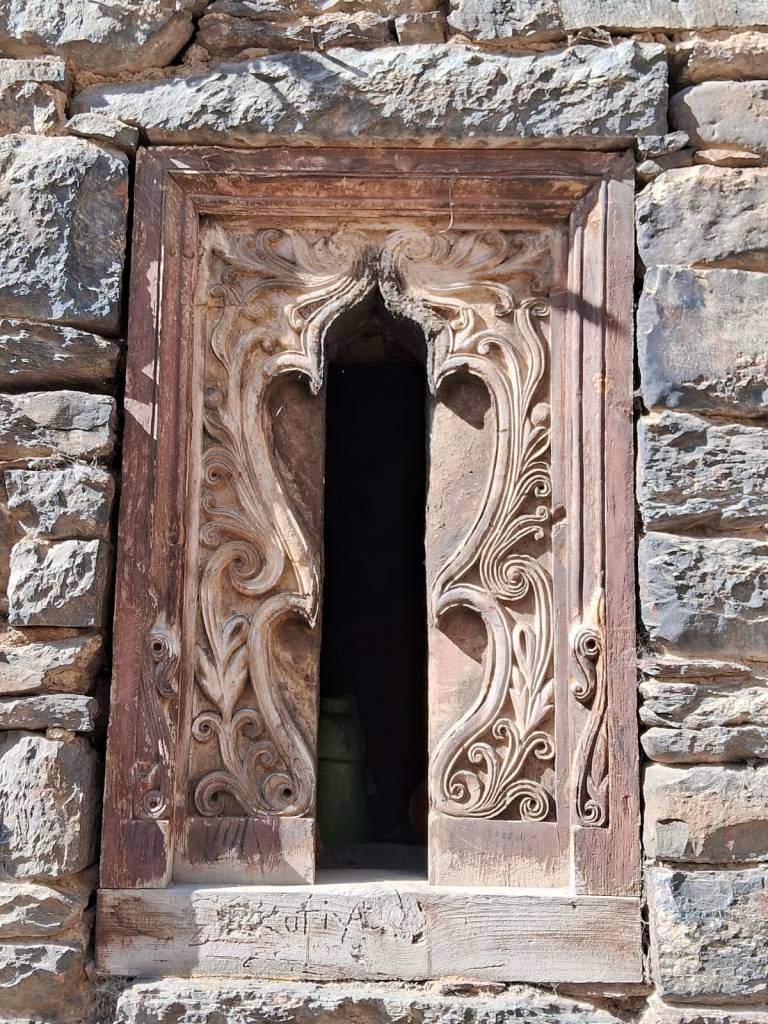

In Kutti village, a local with a stunning 300-year-old home, adorned with traditional carved doors and windows, was planning to demolish it to build a new homestay. The reason: his heritage home lacked an attached bathroom, a basic expectation from tourists today.

Through conversations with several locals, I began to realise that traditional architecture is increasingly seen as obsolete, inefficient, and—above all—not modern.

When I commented to a local guide in Dugtu village that their traditional stone roofs looked so pleasing, I added that they also serve as natural temperature regulators—keeping homes cool in summer and warm in winter, a fact imparted to me by another local. I was admiring the wisdom of this old technology. But he quickly retorted, saying that stone roofs are unreliable during the rains, allowing water to seep through. He preferred tin roofs, a trend gradually replacing the antique stone roofs.

I don’t deny his concern—functionality matters. But must functional always mean ugly? Can’t tin roofs be made more aesthetically compatible—perhaps designed with wood or stone-like textures, or painted in earthy tones that harmonise with the environment?

In the desire to appear “modern,” many villagers imitate diluted versions of urban design aesthetics, often inspired by what they think looks like a trendy resort. The outcome, sadly, is disappointing: homestays that resemble urban slums.

Add to this, the presence of tacky artificial lighting—like the ones wrapped around lampposts in overlit cities—now spilling into villages. These lights don’t enhance the experience; they simply add to the visual pollution and the erosion of natural ambience.

These new structures, packed wall-to-wall with neighbouring houses, are devoid of verandas, landscaping, or spatial breathing room. All elements of grace, proportion, and harmony—once essential to the Himalayan vernacular—are now conveniently sacrificed under the sweeping label of “homestays.”

(I empathise with the locals, they are hardworking and trying their best to provide as much comfort to the tourists with the limited resources they have. Aesthetics apart, I had the best time at Napalchu homestay. My hosts (husband-wife duo) were very dedicated and have kept the place extremely clean and hygienic. The food was delicious too.)

Who says homestays are egregious spaces offering only cheap accommodation and limited comfort? At their best, homestays can be thriving cultural hubs, where tradition, comfort, and cleanliness come together to offer tourists an authentic, immersive experience they will cherish. Something that draws them back. There can be a museum-homestay that displays photos, heirlooms, farming tools, etc., of that village or a homestay with a riverside café built with driftwood, dedicated to river mythology, or a homestay just retaining the original space of how the villagers lived! All it takes is a vision. And that vision shouldn’t rest solely on the shoulders of locals with limited means, it must be supported and enabled by thoughtful governance.

It is the duty of the state to cultivate a unique identity and visual character for each village—or group of villages—rooted in their heritage architecture and traditional spatial aesthetics.

The real risk emerges when homestays, built on allotted land, are designed solely based on individual preferences. The result is a disjointed visual landscape, where each structure follows its own style—often disconnected from the village’s overall heritage character.

Take, for example, the small villages of Gunji and Napalchu in the Vyas Valley—places so breathtaking, they seem to belong more to an artist’s canvas than to the real world. Snow-clad peaks frame the horizon, a river winds gracefully through pine forests, meadows bloom with wildflowers, and terraced farms stretch along the slopes—everything that defines Himalayan serenity.

While soaking in this beauty, I noticed several construction activities taking place on the farmlands overlooking the river. Curious, I asked a local what was being built. “Homestays,” he replied, with a sense of pride. “Next time you visit, you’ll see these fields full of them. Our region is progressing too!”

Yes, surely! I thought. Progress in erosion of landscape, cultural disconnection and loss of farmland!

Take the example of the 11th-century villages of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama in Japan. Nestled in a river valley within the rugged, high-mountain Chūbu region of central Japan, these villages share significant geographic and topographic similarities with many of our own Himalayan settlements.

What sets them apart is their remarkable success in preserving traditional Gasshō-style farmhouses, which remain intact in their original locations. These are a unique farmhouse style that makes use of highly rational structural systems evolved to adapt to the natural environment and site-specific social and economic circumstances. The upkeep of Gasshō-style houses is sustained by traditional communal practices among residents, while Japan’s long-established restoration principles are applied whenever major conservation is required. These efforts prioritise the use of authentic materials and traditional techniques, with strict regulation over the introduction of any modern alternatives.

Notably, the overall layout and infrastructure of these villages—roads, canals, forests, and agricultural fields—have seen no significant change. Even the potential visual disruption caused by a major highway constructed less than a kilometre away has been mitigated through strategic landscaping, including tree plantings, carefully designed embankments, and aesthetic controls on bridge and roadside design to preserve the views from the villages.

In these villages, development pressures are tightly controlled through comprehensive legal frameworks, authorisation procedures, preservation ordinances, and zoning restrictions, all of which place significant constraints on any activity that could alter or degrade the existing landscape.

The ancient wisdom embedded in Himalayan villages—their historic identity, time-tested community management systems, spiritual traditions, healing practices, folklores, local deities, vernacular architecture, and regional cuisines—qualifies many of these remote settlements as not just cultural treasures of India, but as part of the shared heritage of humanity.

If we collectively focus on the following measures, these villages can reclaim their pride, and in doing so, restore our connection to a legacy that defines who we are:

1. Map and Cultivate a Distinct Cultural Identity for Every Village

Each village must be seen not as a replication of another but as a cultural and ecological singularity. This process should begin with detailed ethnographic and architectural research, involving local communities, art historians, artists, and artisans. The outcome should be a village-specific design guideline document that draws upon local tribal and folk traditions—defining architectural forms, proportions, spatial layouts, and culturally rooted elements such as verandas, courtyards, roofing styles, and decorative details.

Additionally, the colour palette should be inspired by native flora, rivers, earth and the sky, so that the built environment harmonises visually with the landscape and seasons, enhancing both aesthetic cohesion and cultural continuity.

2. Establish Restrictions on Construction Materials and Promote Energy-Conscious Models

Villages should adopt a new paradigm of climate- and culture-sensitive construction, one that prioritises locally sourced, sustainable materials such as stone, timber, slate, lime plaster, and mud. These not only reflect the vernacular identity but also provide thermal efficiency, seismic resilience, and ecological sensitivity.

Architectural designs should emphasise natural lighting, cross ventilation, and optimal space utilisation, minimising dependence on energy-intensive systems. In water-scarce areas, compost toilets and greywater reuse systems should be encouraged to preserve local water ecology.

In cases of restoration, renovation, or necessary modernisation, hybrid models can be adopted, where modern structural materials are discretely integrated to provide stability and durability without compromising the aesthetic and spatial integrity of the traditional built environment.

3. Revive and Repurpose Local Craftsmanship

Traditional skills such as carpentry, wood carving, and stone masonry should be integrated into contemporary village architecture to ensure cultural continuity and provide sustainable livelihoods to local artisans. These crafts can be meaningfully applied in:

- Window frames and jharokhas

- Ornamental lintels and entrance doors

- Stone inlay on pathways and courtyards, featuring motifs and folk symbols unique to the region

This approach honours heritage while adding tangible value to the built environment.

4. Incentivise Restoration Over Demolition

Instead of replacing heritage homes with generic concrete structures, financial incentives such as grants, subsidies, or tax rebates should be offered to encourage villagers to restore and adapt existing traditional houses. A prime example is the 300-year-old home in Kutti, which, with thoughtful restoration, could become a model of adaptive reuse—preserving history while meeting modern needs.

5. Cluster-Based Development Plans

To avoid the unregulated sprawl of individually scattered houses, villages should adopt cluster-based zoning that promotes thoughtful spatial organisation and architectural cohesion. This approach supports both aesthetic harmony and infrastructure efficiency. Key elements of this model include:

- Homestays grouped around a shared courtyard, central green, or village chowk, fostering community interaction and reinforcing traditional social patterns.

- Shared public infrastructure—such as toilets, kitchens, solar charging stations, and waste management systems—within each cluster. This reduces visual clutter, lowers material usage, and optimises resource allocation.

- Vegetative buffers or green belts between clusters to maintain the village’s natural rhythm, visual scale, and ecological balance.

Such a system supports a more controlled flow of tourism, offering both community hospitality and quiet pockets of solitude in nature. It aligns well with the needs of visitors seeking immersive experiences without compromising the serenity or sustainability of the village environment.

Some noteworthy examples of cluster-based development can be seen in the Alpine villages of Switzerland. These towns have been meticulously planned with compact village centres and strict restrictions on scattered or haphazard development.

New construction in these areas must comply with stringent architectural guidelines that ensure stylistic continuity with existing buildings, preserving the visual integrity and traditional charm of the settlement. Tourism infrastructure such as hotels, cafés, and shops is thoughtfully concentrated around pedestrian-friendly plazas, maintaining a vibrant yet walkable hub.

Importantly, these villages are surrounded by uninterrupted natural landscapes—from pastures and forests to skiing trails—safeguarding the ecological rhythm and scenic beauty that define their identity.

6. Land Ownership and Selling Rights

One of the key factors contributing to the aesthetic and cultural disintegration of Himalayan villages is the unregulated sale of land to outsiders, often individuals or entities with no connection to the region’s landscape, culture, or sensibilities. This has led to the construction of developments that mimic plains-based resort models, often completely out of sync with the ecological and cultural context of the mountains.

A glaring example was the attempted construction of an infinity-like swimming pool overlooking Rudraprayag—a disturbing sight in a sacred valley known more for spiritual depth than for luxury tourism.

Mountain tourism is not leisure tourism. It serves a different purpose. It is about self-discovery, immersion in nature, clean air, silence, and the wisdom of mountain life. It is about learning from the environment, the people, and their enduring cultural legacy.

When people lacking this mountain consciousness purchase land purely for commercial gain, they do not build heritage—they build infrastructure. They do not preserve a culture—they replicate what is already abundant elsewhere, and in doing so, they dilute the very soul of the mountains.

Land rights in sensitive regions must therefore be regulated. Ownership, especially for tourism development, should come with clear responsibilities for cultural and ecological preservation, and ideally involve local partnerships that embed respect for regional identity.

Unfortunately, what I observed during my trip is that local sensibilities, too, are drifting away from their own traditions and ecological wisdom, increasingly influenced by urban aesthetics and commercial notions of appeal. In Nabi village, I came across a few homestays attempting to showcase their culture, but this was reduced to a framed photograph of a local man in traditional attire, placed like a decorative prop. A few others displayed images of deities as their idea of aesthetic expression, as if that alone could embody the richness of Himalayan heritage.

7. Training and Design Outreach

To ensure sustainable and aesthetically rooted development, it is essential to build the capacity of local communities in culturally aligned and environmentally sensitive construction practices.

Training camps should be regularly organised for masons, carpenters, artisans, and villagers, where they are introduced to principles of design, aesthetics, spatial harmony, and the significance of traditional architecture. These sessions can include exposure to case studies from global heritage villages, helping them visualise how tradition and modernity can co-exist with dignity and functionality.

In addition, a dedicated digital platform or mobile app should be developed, offering design templates, hand-drawn sketches, material recommendations, and budget-friendly construction ideas, tailored specifically for mountain terrains and climates. A helpline service can further assist locals in accessing real-time design support and troubleshooting guidance during construction or renovation work.

This outreach initiative would empower locals to become stewards of their own heritage, ensuring that development is not imposed from outside but emerges from within the community, with knowledge, pride, and aesthetic coherence.

8. Village Economy

Each village should include an Artistic and Cultural Centre as part of its development code—a multifunctional space that serves as both a museum and a community-run souvenir shop. This centre would document and display the village’s unique history, customs, spiritual practices, crafts, and oral traditions, offering visitors a deeper understanding of the place beyond its scenic beauty.

Locally made handicrafts, textiles, artworks, herbs, and traditional products can be displayed and sold within the space, transforming heritage into livelihood. The profits generated should be equitably shared among community members, with part of the revenue reinvested into the upkeep of the centre, local schools, or public infrastructure.

This model not only preserves the cultural fabric of the village, but also empowers residents by creating sustainable, community-owned micro-economies tied directly to their identity and landscape.

9. Regulating Tourist Flow

To preserve the integrity and tranquillity of heritage villages, it is essential to regulate the volume of tourist traffic within any given time. A well-managed visitor cap, based on the village’s carrying capacity, can be implemented through a permit or time-slot system, especially during peak seasons. Digital registration platforms or mobile apps can help streamline this process, allowing for fair access while avoiding overcrowding.

10. No tourism zones

Despite the best intentions and precautionary measures, once pristine Himalayan regions are opened to tourism, they inevitably face environmental degradation, waste accumulation, and a loss of sacredness. Not every corner of the Himalayas is meant for sightseeing or recreation.

Certain landscapes are deeply sacred, contemplative, and energetically potent—serving as spaces for spiritual practitioners, ascetics, and yogis who seek solitude and silence. The carbon footprints, noise, and casual intrusion of tourism risk disrupting the delicate spiritual ecology of these regions.

To preserve their sanctity, biodiversity, and cultural mystery, specific zones across the Himalayas should be officially declared No-Tourism Areas. These restrictions must be legally protected and monitored by local custodians and environmental bodies, recognising that preservation sometimes means saying no, not just to mass tourism, but to access itself.

Without deliberate efforts to preserve their heritage and environment through mindful aesthetic and spatial stewardship, these fairy tale villages risk losing the very essence that makes them special, becoming indistinguishable from countless other rapidly urbanising towns, becoming ‘Once upon a time’ tales—lost to future generations.

Leave a comment