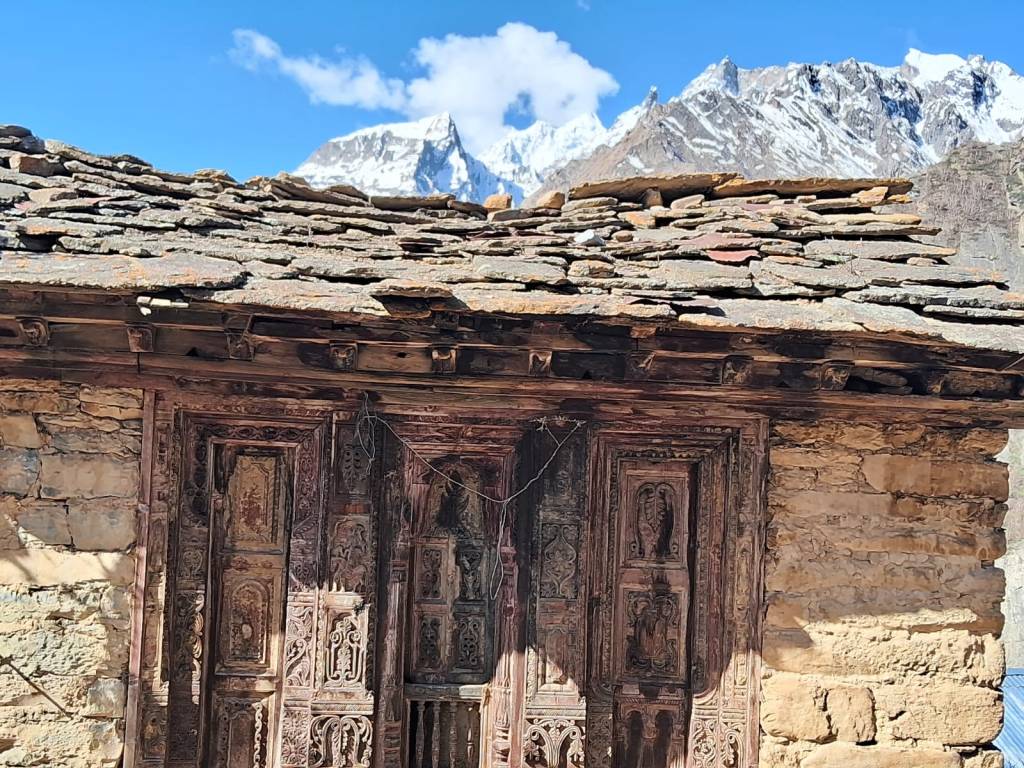

Behind the beautiful mountains, blue skies, lush green meadows, snow clad peaks, there’s a secret hiding. A secret that, once revealed, draws us closer to the truth. Now, that secret is out in the open.

A pile of trash lying in all its glory. This is Kuti village, the most beautiful place on my journey towards Adi Kailash. The same secret was found littering the villages of Gunji, Napalchu and Nabi. I don’t blame the villagers. It is the lack of administration in trash management in remote villages.

As a result, the trash ends up in the river, the valley—everywhere. I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes. A trash truck in Dharchula emptied its entire load straight into the valley—into the pristine Kali river. I was so stunned, I couldn’t even ask the driver to stop the car and record the shocking sight.

My own driver, munching on a chocolate and casually tossing the wrapper out the window, tried to reassure me: “Don’t worry, it doesn’t reach the river. It gets stuck in the bushes.”

Sensing my disbelief, the local guide chimed in, “Don’t worry, they’ll soon cover the trash with mud.”

But it wasn’t the gravity-defying logic of the locals that troubled me most—it was the unwavering confidence of the local administration in this blasphemous method of waste disposal.

While the beauty of the Himalayas kept pushing the horror I just witnessed, it kept resurfacing—at every stop along my journey. Not even the pristine Parvati Sarovar, perched at 4,497 meters and overlooking the majestic Adi Kailash, was spared. I found myself picking up agarbatti packets, matchboxes, food wrappers, plastic bottles, caps—scattered along its banks. The edge of the lake was blackened, bubbling like drain water.

If packaged drinking water and food can make their way up to the remotest villages, then their empty wrappers and bottles can surely make their way back down (not through rivers, of course) for proper disposal until some concrete trash management is in place.

At one of the dhabas, I noticed a pile of plastic bottles accumulated in a corner. Curious, I asked a young girl working there—home for the holidays from her studies in Pithoragarh, helping her father. She told me her father digs a pit and fills it with the bottles, unlike others in the area who simply toss the trash around.

On one of my treks near Narayan Ashram, I collected a good amount of trash scattered across the valley and asked the property’s caretaker where I could dispose of it. He casually gestured toward the edge of the cliff. His message was clear: throw it back into the valley.

I was informed by the local who has a homestay in Dharchula that the toilet water of the city is directly let out into the river. There are no sewage treatment plants.

Later, when I entered Almora town, I wasn’t greeted by crisp mountain air or blooming forest scents. Instead, I was welcomed by the stench of open garbage, sitting like a rotting wound on the edge of the town.

I remember holding on to the eaten kafal seeds for over 50 kilometres because I couldn’t find a proper dustbin. “Proper” being the operative word—my driver would stop at various points he considered ‘proper’, where trash had been casually heaped: on the tin roofs of closed shops, at the corners of roadside stalls, or simply dumped along the roadside. But I refused to add to the mess. It wasn’t until we reached Dharchula that I finally came across a proper waste container—and only then did I let them go.

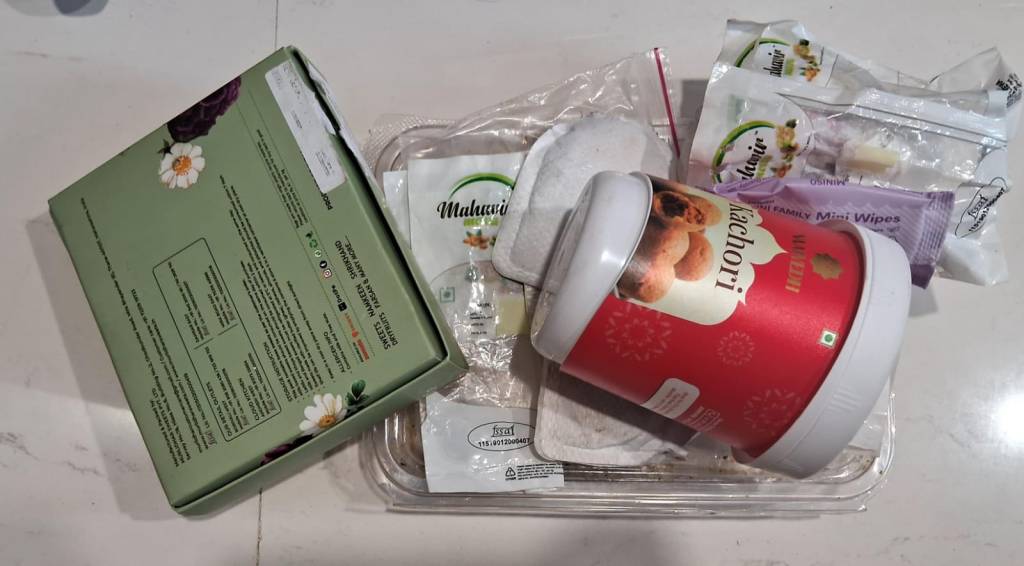

I carried the empty snacks wrappers and packaging back home. Because what I mostly saw in the mountains was trash being either burnt or flung into the valleys. This was my choice—and I’m not asking anyone else to do the same. Unless, of course, you share the same kind of insanity… or perhaps, sanity… as I do.

Trash isn’t just unsightly or pollutive, it can alter entire ecosystems. The leftover food and litter attract predators that compete with the natural flora and fauna, degrade their pollination and seed dispersal, and disrupt natural predator–prey interactions. These invasive species displace native fauna and flora, reduce habitat quality, and can trigger long-term ecosystem change.

The widespread availability of litter invites wild species, including bears, elephants, storks, and crows, putting them at significant risk from plastic ingestion. Animals reliant on human waste lose fear of humans, increasing conflict and risk to both sides.

The Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), a subspecies of the brown bear with only 500 to 750 remaining in the wild, has faced increasing threats from human plastic consumption since the early 2000s. Recent studies suggest that 75% of the bears’ diet now consists of scavenged waste from human dump sites. Plastic waste contains harmful chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA), which can negatively affect animal health, reproduction, neurological systems, embryonic development, and mortality rates. Pathogens, such as Salmonella, and zoonotic diseases (which can be transferred from animals to humans) are also commonly found in waste dumps.

During my visit to Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, I came across the Crumb Clean Campaign—an initiative addressing a similar issue of parasitic intrusion caused by leftover food brought in by visitors. The campaign urged people to ensure no trace of food was left behind, not even a single crumb on the picnic tables, in order to protect the endangered marbled murrelet from an increase in predatory species drawn by human food waste.

What I witnessed was remarkable. The park was spotlessly clean—no litter, no food waste, not even a stray wrapper. Surprisingly, there were no anti-litter signboards or warnings of fines. There were no food stalls scattered across the grounds, only a single ice cream kiosk. A designated picnic area with wooden tables sat neatly in a quiet corner of the park, and that was the only place food was allowed.

We had packed a full Indian feast—chole bhature, biryani, and pav bhaji—and noticed that, like us, every visitor took care to leave the table spotless. (There was, of course, no waiter to clean up after us, unlike the norm back home.) The dustbins were clean, discreet, and not overflowing with trash clumsily stuffed around their rims.

The park proudly claimed to be “crumb-free”, and looking around, it seemed a genuinely earned badge. Whether it was the self-discipline of the visitors or the thoughtful management of the park—or perhaps both—it was clear that tourism and cleanliness can, in fact, go hand in hand.

If a crumb-free redwood forest is possible, why not a wrapper-free Himalayan meadow?

In fact, trash-free Himalayas already exist—in parts of Ladakh and the northeastern frontiers. Cities like Gangtok in Sikkim and Shillong in Meghalaya consistently earn praise as some of the cleanest in India. Mawlynnong village, located around 90 kilometres from Shillong, won the accolades for being the Cleanest Village in Asia in 2003 and the Cleanest Village in India in 2005.

Leh, the heart of Ladakh, holds the distinction of being its cleanest city and was ranked among India’s top 100 cleanest under the Swachh Bharat Mission.

A friend once shared a striking story from her trip to Ladakh: her young daughter, having finished a chocolate, threw the wrapper out of the car window. The driver immediately stopped, got out, and walked back to retrieve it from the roadside. That small act spoke volumes—it reflected a local culture where cleanliness is not enforced, but deeply respected.

Trash-free mountains are not a utopian dream—they’re a reality in places where locals and tourists align in their commitment to hygiene, sustainability, and care for the land.

Unfortunately, with the boom in tourism, pilgrimage, and trekking, these pristine landscapes are increasingly being choked by waste. Managing trash here is not just a logistical challenge, but a cultural and ecological necessity. We can’t afford to wait for government to finally wake up and sanitise our sacred hills.

Here are some key measures that can be taken to address the problem meaningfully:

1. Student-Led Research & Institutional Engagement

Universities and research institutes should step beyond academics and lead actionable projects in mountain waste management.

- Develop eco-labs in mountain regions that focus on biodegradable packaging, eco-bricks, and organic waste reuse.

- Conduct field research projects involving environmental science, urban design, and policy students to analyze waste patterns.

- Launch adoption programs where universities “adopt” a mountain village to guide sustainable development.

2. Community-Based Waste Enterprises

Locals are key stakeholders. Creating community-led waste enterprises can turn trash into a livelihood opportunity.

- Train and employ village youth in waste segregation, composting, and recycling.

- Encourage production of handicrafts or construction materials from upcycled waste.

- Organize zero-litter village competitions backed by local panchayats and NGOs.

3. Mandated Environmental Messaging in Travel Content

Travel vloggers, bloggers, and influencers who film in the mountains should include mandatory no-litter messaging in their content.

- Platforms can collaborate with tourism boards to enforce a “Clean Himalayas” label for creators who follow and promote sustainable practices.

- Tourism departments can run ambassador programs with popular content creators.

4. Festivals & Clean-Up Events for Awareness

Use the power of community and celebration.

- Organize eco-fests in villages that blend cultural activities with trash clean-up drives, workshops on waste reuse, and competitions.

- Engage tourists in volunteer-for-a-day clean-up events as part of their itinerary.

5. Policy-Level Interventions

- The wastewater should be treated before being let into the rivers. There should be sewage treatment plants.

- Impose strict plastic carry bans beyond certain altitudes, with local checkpoints.

- Require all tourism companies to carry back the trash they bring, under a “pack-in, pack-out” policy.

- Use QR-coded permits for tourists to track and audit trash they produce (a model already piloted in some regions).

- Install water purifiers and clean drinking water filling stations so that the use of packaged drinking water can be eliminated.

- No carrying any disposable styrofoam plates, glasses, spoons, etc. (These eventually get dumped into the valley or burned)

6. On-Ground Eco Infrastructure

- Build waste stations every few kilometers on popular treks.

- Install bio-digesters and compost pits at homestays and dhabas.

7. Digital Reporting and Gamification

- Create a mobile app or WhatsApp bot where trekkers can report waste zones or litter spots.

- Use gamification to reward repeat travelers and locals who consistently engage in clean-up or report violations.

8. Curriculum Integration

- Add waste literacy modules in school curriculum of mountain districts.

- Conduct poster-making, eco-storytelling, and walk-the-talk workshops in schools with visiting volunteers or travellers.

Trash management is not merely about cleanup; it’s about respect, stewardship, and long-term vision. It is an exigency of the mountains. One can only hope its alarming bells awaken tourists, locals and governance alike.

Leave a comment